|

|

PENN STATE RESEARCH: TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER

A STATUS REPORT TO THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

by

Eva J. Pell, Vice President for Research

January 19, 2001

Good morning. Last Spring Ted Junker and Joel Myers

asked me to plan to provide you with an overview of our efforts in Tech

Transfer; I am very pleased to do so. When I came to the Research Office,

Tech Transfer was the area least familiar to me; and I wasn’t sure how I

would take to it. However, it has turned out to be a challenging,

fascinating area; and one that offers Penn State enormous opportunities. I

have invited Dr. Gary Weber, Assistant Vice President for Research and

Director of Technology Transfer, to join me at the podium. We decided that

it might be easiest to listen to one presenter, so I will provide the

overview of our enterprise and then we will both field your questions as

appropriate.

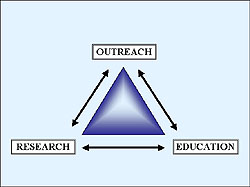

Last year we began the research presentation

with our equilateral triangle. You may recall that we spoke of the three

missions of the University - Outreach, Education, and Research as the arms

of this triangle, with the connections reflecting the integral

relationship amongst these activities. Today, as we make Technology

Transfer the focus of our discussion, we will again begin with the

triangle this time having rotated it to place outreach at the top of the

screen. Last year we began the research presentation

with our equilateral triangle. You may recall that we spoke of the three

missions of the University - Outreach, Education, and Research as the arms

of this triangle, with the connections reflecting the integral

relationship amongst these activities. Today, as we make Technology

Transfer the focus of our discussion, we will again begin with the

triangle this time having rotated it to place outreach at the top of the

screen.

Tech transfer is defined as those activities that facilitate the

process whereby the University’s creative and scholarly works may be put

to public use and/or commercial application.

Penn State has historically sought the full and rapid dissemination of

the creative and scholarly works of its faculty, staff, and students in

order to provide timely benefits to the citizens of the Commonwealth and

the Nation. In the United States most of the basic research and

development of fundamental concepts occur in universities, federal

laboratories, and a number of large corporations. Industries largely have

concentrated on the later phases of the R&D process. Thus,

universities are major sources of the new knowledge that underlies novel

commercial concepts, products, and processes.

There are several reasons why Universities, particularly Land Grant

Universities, should be involved in Tech Transfer. As you will see in this

presentation, - just as with more basic aspects of research, - so Tech

Transfer provides unique opportunities for graduate and undergraduate

students; Tech Transfer clearly leads to opportunities for economic

development; and there is a federal mandate to transfer technology.

Until 1980, the federal government owned about 30,000 patents, many of

which had resulted directly from research conducted at universities; and

only a small percentage ever became commercialized. On December 12, 1980,

the "Patent and Trademark Act Amendments of 1980", also known as the

Bayh-Dole Act, were enacted to create a uniform patent policy among the

many federal agencies that fund research, and to create an environment

more likely to foster commercialization of the patents the federal

government had seeded through its financial support. Bayh-Dole enables

small businesses and non-profit organizations, including universities, to

retain title to materials and products they invent under federal funding.

By placing few restrictions on the universities’ licensing activities,

Congress left the success or failure of patent licensing up to the

institutions themselves. The success of Bayh-Dole in expediting the

commercialization of federally funded university patents is reflected in

the statistics. Prior to 1981, fewer than 250 patents were issued to

universities per year. By 1993, almost 1,600 were being issued each year.

Of those, nearly eighty percent stemmed from federally funded research.

With the increased emphasis on development of intellectual property, in

May 1987 the Board of Trustees of The Pennsylvania State University took

action wherein the Board directed the University to undertake an

eight-point initiative to strengthen Penn State’s contributions to the

economic development of Pennsylvania. I would like to take a few minutes

to review with you, your charge to us. The officers of the University were

to develop specific programs as follow:

- A program to strengthen advisory and consultative services to

government to assist in the formulation and implementation of necessary

public policies and programs to foster economic growth, job creation,

maintenance of adequate infrastructure and preservation and restoration

of environmental quality.

- A program for the orderly use of University lands for the

development of researchÑoffice parks, business incubators, conference

center, and other potential uses.

- A program to promote a business sensitive environment within the

University, which facilitates access and supportive relationships

between the academic and industrial communities.

- A program to assess potential venture capital and equity investments

by the University to promote economic development.

- A program to establish, maintain and strengthen state-of-the-art

University facilities for research and technology transfer.

- A program to coordinate existing programs and activities that relate

to economic development in order to maximize their effectiveness.

- A program to encourage and assist faculty, staff and students to

engage in entrepreneurial activities related to University research

activities.

- A program to build recognition for and support of an active role for

the University in the economic development of Pennsylvania.

We have made significant strides in all eight of these

programmatic elements. Today we will focus on our Intellectual Property —

how we manage it and how we are doing. By the end of this presentation I

hope you will share my enthusiasm for the value of this enterprise to our

tripartite mission.

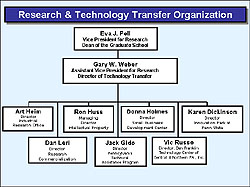

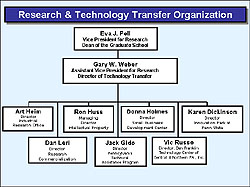

Before continuing I would like to give you a sense of how we are

organized and introduce to you the key players. I have already introduced

Gary Weber to you. Gary, who came to us from PPG where he served as Senior

Vice President for Science and Technology, heads up our team of

professionals who work with businesses and industries in Pennsylvania,

across our nation, and around the world.

Art Heim is Director of our Industrial Research Office. Art and his

staff link companies with appropriate faculty and research centers.

Currently, Penn State has master agreements with 14 major industrial

partners, such as Air Products, Berg Electronics, Ford Motor Company, and

Hershey Foods Corporation.

Dan Leri is Director of our Research Commercialization Office. Dan

promotes the start up of new companies by helping faculty and staff secure

funding from multiple sources of early stage capital, such as seed

funding, angel investors, and venture capital funds, and identifies

mentors and management team members.

Ron Huss is Director of our Intellectual Property Office, the IPO. Ron

and his staff are responsible for the management of intellectual property,

including the patents, trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets.

Jack Gido is Director of PENNTAP, the Pennsylvania Technical Assistance

Program, a state-related program with a network of technical specialists

throughout the Commonwealth that provides free scientific and

technological assistance to Pennsylvania’s smaller businesses to improve

their competitiveness.

Donna Holmes is Director of the Small Business Development Center, part

of a national network of more than 950 centers, 16 of which are based at

colleges and universities in the Commonwealth. These centers provide

guidance in obtaining SBA loans and in managing small businesses.

Vic Russo is Director of the Ben Franklin Technology Center of Central

and Northern Pennsylvania, one of four regional centers of the

Commonwealth’s Ben Franklin Partnerships. Ben Franklin provides financial

support, technology and management experience, and ways to link public,

private, and educational resources to help strengthen the high technology

components of the state’s economy.

Karen Dickinson is the Director of Innovation Park at Penn State

(formerly known as the Research Park). The success of Innovation Park is

an integral part of our vision for technology transfer and development at

Penn State as I will discuss later.

Penn State’s Intellectual Property Office the IPO, is

comprised of a director, a number of technology licensing officers (TLOs)

and associated staff support. We engage students at every level to assist

in various aspects of the work of the office. Undergraduate students in

the Eberly College of Science assist TLOs with technical assessments and

evaluations of invention disclosures. The IPO has interns from the MBA

program assisting with business issues associated with intellectual

property management, including assessment of marketability of inventions.

The IPO has had several Dickinson School of Law summer interns assist with

analysis of legal agreements and inventorship, patent searches, assessment

of patentability, and review of patent case law.  One of the former interns, Livinia Jones, is now a registered

patent attorney; she was hired by McQuaide Blasko and works closely with

Mark Righter, our attorney of many years. This spring we are embarking on

an interesting experiment. Four undergraduate students from the Department

of English will intern in IPO during the spring and summer semesters. Don

Bialostosky, the Head of the English Department, and Gary Weber conceived

of the idea of utilizing English students skilled in parsing, reading and

understanding complex literature to assist IPO staff in tracking key

concepts through multiple drafts of complex and lengthy agreements,

especially licenses. As we all know, there are many outlets for the

talents of students in English and we hope to open the eyes of some of

these students to a very interesting set of possibilities. One of the former interns, Livinia Jones, is now a registered

patent attorney; she was hired by McQuaide Blasko and works closely with

Mark Righter, our attorney of many years. This spring we are embarking on

an interesting experiment. Four undergraduate students from the Department

of English will intern in IPO during the spring and summer semesters. Don

Bialostosky, the Head of the English Department, and Gary Weber conceived

of the idea of utilizing English students skilled in parsing, reading and

understanding complex literature to assist IPO staff in tracking key

concepts through multiple drafts of complex and lengthy agreements,

especially licenses. As we all know, there are many outlets for the

talents of students in English and we hope to open the eyes of some of

these students to a very interesting set of possibilities.

To understand how we manage intellectual property, we should say a word

about the Penn State Research Foundation known as PSRF. PSRF, so named in

1992, is a subsidiary of The Corporation for Penn State. PSRF is

responsible for managing our intellectual property portfolio, - overseeing

the costs of protecting, litigating and maintaining patents. PSRF is also

responsible for the distribution of royalties and other revenues

associated with the inventions generated by our faculty and staff as you

will see in details to follow. PSRF is governed by a board of up to 15

members.

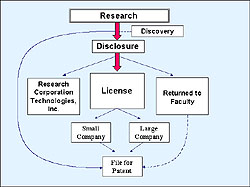

Now, I would like to take you through the intellectual property process

from the moment a faculty member is hired. One of the many forms that new

faculty, staff, and graduate students sign when starting employment at

Penn State is the "University Intellectual Property Agreement Form". This

agreement assigns to the University all rights that may be acquired in

inventions, discoveries, or rights of patent, which are conceived or

first, actually reduced-to-practice using University facilities or

resources or are in the field of expertise and/or within the scope of

responsibilities covered by employment, appointment, and or association

with the University.

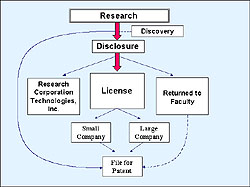

It is the responsibility of the technology transfer arm of the Research

Office to provide cradle to adulthood service to University personnel as

they develop intellectual property. The first step in this process is the

discovery that occurs during execution of a grant or contract. At this

point University personnel are enjoined by the terms of the Intellectual

Property Agreement to disclose to the University any intellectual property

developed. To do this, an "Invention Disclosure" form is submitted to the

IPO.

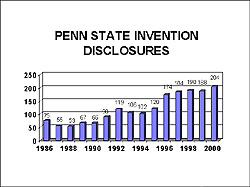

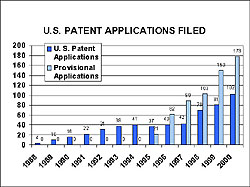

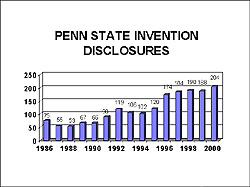

As shown in this slide (below), the number of invention

disclosures has increased markedly in recent years; for the year 2000, 204

disclosures were received. I would like to present a brief description of

a few of the discoveries that have reached the disclosure stage:

- "In situ delivery of ceramide analogues as a novel preventive

therapy for restenosis" is a technology that uses a naturally occurring

lipid to coat implantable devices, such as stents, thus, preventing

reclosure of vessels after angioplasty. The inventor is Professor Mark

Kestor in the Department of Pharmacology in our College of Medicine. A

patent is now pending.

- "Wireless infrared multi-spot diffusing communications system", is

an approach which uses infrared waves when radio frequency is not

appropriate. As an example, this technology is being explored for use

inside the Pittsburgh airport. The inventor is Professor Mohsen Kavehrad

in the Department of Electrical Engineering.

- "High efficiency moving magnet loudspeaker" is a technology in which

refrigeration uses sound waves rather than conventional electricity. A

number of companies are looking at this technology for use in deli cases

and with frozen foods. The inventor is Steven Garrett Senior Scientist

at the Applied Research Laboratory and Professor of Acoustics. A patent

is now pending.

Upon receipt of the disclosure form, the Intellectual Property Office

screens the inventions and discoveries for patentability, commercial

potential, and marketability. The IPO then attempts to find a licensee

willing to underwrite both the cost of patent prosecution and any further

research required to bring a concept to the stage of commercialization.

The marketing process itself sets the value of the technology.

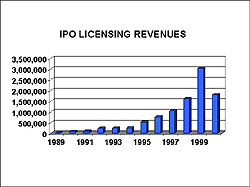

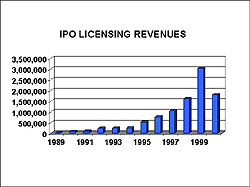

As you see in this slide (below), PSRFs licensing

revenue seems to have fallen drastically when compared to 1999. Our 1999

revenues were exceptionally high due to the liquidation of $1.4-million in

stock. If you remove the stock liquidation from the 1999 figure, the

licensing revenues for 2000 were up by about nine percent. As you will see

in the discussion to follow, we currently hold equity in several companies

that have licensed our technology. Thus, in the future we again will

realize significant leaps forward in licensing revenues.

In the best case, the technology is licensed to a large

or small company and that entity will take on the fiscal responsibility of

patenting the intellectual property. Alternatively, we may elect to patent

the intellectual property ourselves, if we believe that the technology has

great commercial potential and a licensee is not immediately apparent. In

cases where commercial potential has not been identified through these

processes, we ask Research Corporation Technologies in Arizona to try and

find a company interested in licensing the technology. If no licensee is

found, we attempt to get funding agency approval to return the technology

to the inventor, enabling the inventor to pursue the technology using his

or her own personal resources.

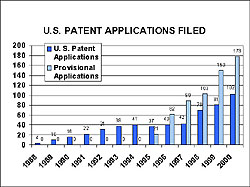

If the University’s decision is to patent, a provisional

patent application is filed and a $75 fee is paid, giving Penn State full

U.S. and international patent protection for one year. Conversion of the

provisional patent application to a full U.S. patent application costs on

average $16,500 and takes 2-3 years to complete, but the invention is

protected throughout this process. If a licensee is found for the

invention, every effort is made to have the licensee pay or reimburse the

University for patent expenses. For the year 2000, the IPO filed 178 U.S.

provisional patent applications, and filed 102 full U.S. patent

applications. During 2000, 44 U.S. patents were issued to Penn State

bringing our total issued patents to 223.

Within 30 months from the time the provisional patent

application is filed, the decision must be made whether or not to obtain

foreign patent protection and, if so, in which countries. The University

only files for foreign patent rights if the licensee is willing to pay the

costs associated with this process - which can cost $50-$100,000 - with

filings usually taking place in Europe, Canada, and Japan. Some countries,

particularly in the developing world, do not honor patents.

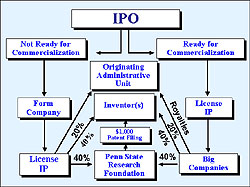

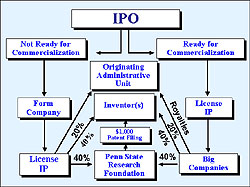

At the time that technology is patented, $1,000 is provided by PSRF to

the inventor or inventors. This is an ideal time to determine the

distribution pattern, as it is a lot easier for inventors to agree on

distribution of $1,000 than $100,000. When royalties are distributed or

equity liquidated, all the expenses incurred by PSRF are reimbursed. Once

reimbursements have been honored, PSRF retains 40% of the remainer, and

disburses 40% to the inventor or inventors, and 20% to the administrative

unit of origin.

Let’s take a look at a few examples of our top royalty

producing technologies:

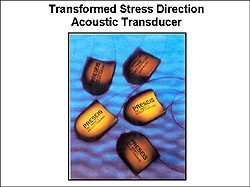

- "Transformed stress direction acoustic transducer", was invented by

Drs. Robert Newnham, Shoko Yoshikawa, and Qi Chang Xu, and licensed to

Input/Output, Inc. This invention is a compact, highly reliable

transducer, capable of functioning in hostile environments such as those

found in arenas including: under water petroleum exploration detectors,

fish finders, optical scanner units, and ink jet printers. To date, PSRF

has received just over $395,500 in revenue.

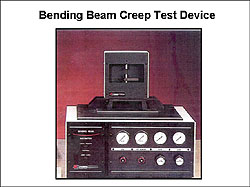

- The "Bending beam creep test device" invented by Dr. David Anderson

and his colleagues in the Pennsylvania Transportation Institute and

College of Engineering, and licensed to Cannon Instrument Company, is a

unit used to measure the flow properties of asphalt cement. This

invention has produced $237,000 in revenues.

- "Pelletized mulch" invented by George Hamilton in the College of

Agricultural Sciences, and licensed to Lebanon Chemical Company is sold

under the name "PennMulch". This product, made from shredded newsprint

or other recycled paper, is used to cover newly seeded turfgrass on golf

courses, home lawns, sports fields and other turf areas. To date, this

invention has produced $212,000 in revenues.

- "Microwave Sintering of Tungsten Carbide" is a technology based on a

series of patented inventions by Rustum Roy, Dinesh Agrawal, Jiping

Chang, Mahlon Dennis, and Paul Gigil of the Materials Reserach

Laboratory and licensed to Dennis Tool Company. This technology uses

microwaves rather than traditional heating techniques to create

superhard materials for machining and wearing surfaces. To date, PSRF

has received $105,000 in revenues.

Historically two of our most successful patents come from the College

of Agricultural Sciences:

- Our top revenue-producer to date is the "delayed release mushroom

nutrient", invented by Professor Lee Schisler and his graduate student,

David Carroll and licensed to Spawnmate, Inc. This discovery enhanced

the growth of mushrooms and provided PSRF with $2.7-million in revenue.

Both the patent and the license have expired.

- "Creeping bentgrass" was discovered by Professor Joseph Duich and

licensed to the Penncross Bentgrass Association. The development of

turfgrass varieties, of which the "first varieties" produced revenues

amounting to over $2.3-million. The "second varieties" have been added

and have produced $110,000 in revenues to date.

Licensing decisions are dictated by the University’s obligation to

transfer technology in a way that benefits society. This necessitates that

licensees have resources to successfully commercialize the technologies in

question. Where these conditions are met, the University may agree to

accept an equity position in a company in lieu of a licensing fee and/or

sales-based royalty arrangement.

I would like to take a few minutes to discuss with you three

inventions, or sets of inventions for which we have accepted equity in

lieu of royalties.

Last year during our presentation on Research we talked about the

establishment of EIEICO, a company launched by private investors. The

company began with an initial investment of $3 million; PSRF received 22%

equity in the company. Three agricultural technologies, one a genetic

marker for boar taint (the unpleasant odor associated with pigs), the

second a technology dealing with artificial insemination of ruminants, and

the third a poultry feed supplement, were bundled together to form this

start up company located in Centre County. Since the contract was signed

two exclusive sublicensing agreements have been signed with large

agricultural industries, a $365,702 research contract has been executed

with the University allowing for employment of a postdoctoral fellow in

the College of Agricultural Sciences, and a research laboratory has been

established at Zetachron, one of our incubators.

Chiral Quest LLC. is a company based on technologies developed by

Professor Xumu Zhang of the Department of Chemistry. A word about the

technology; many compounds are synthesized and although the product is

pure chemically, the product may have different configurations. Often only

one configuration will be effective for a designated purpose, for example,

as a pharmaceutical; and in the worse case scenario other configurations

may be toxic. Dr. Zhang has developed families of catalysts capable of

"locking" chemicals into a single, desired configuration. Eight catalyst

families consisting of 13 invention disclosures and multiple patent

applications have recently been licensed to Chiral Quest LLC, a start-up

company organized by Technology Assessment and Development, Inc., a State

College company. PSRF will receive ten percent equity in Chiral Quest for

the licensing rights. Development of the technologies will continue both

in Professor Zhang’s laboratory within the University and in Chiral

Quest’s laboratory in the Zetachron building. It is Chiral Quest’s

intention to license this Penn State technology widely throughout the

pharmaceutical and possibly agricultural and chemical industries.

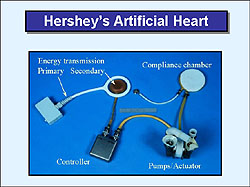

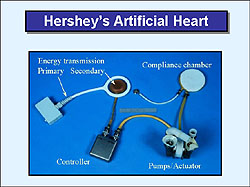

Another example is the artificial heart developed at Hershey

Medical Center. William Pierce, Emeritus Evan Pugh Professor of Surgery,

Gerson Rosenberg, Professor of Surgery and Chief of the Division of

Artificial Organs, and their team developed a total artificial heart that

can be implanted in the space created by removal of the patient’s heart.

The system also uses an implanted controller and energy transmission

system. This invention stems from a 25-year-old research activity at Penn

State funded for many years by NIH. Because this technology is now so

advanced, NIH will no longer continue to support development of this

device. Fortunately, an industrial partner and recognized leader in the

field, ABIOMED, was identified to help Penn State researchers continue

their work as they move toward clinical trials of the device. ABIOMED will

have exclusive rights to the Penn State Heart and will have access to

future advances in related implantable replacement heart technology. The

terms of the transaction consisted of payment to PSRF by ABIOMED of 60,000

shares of common stock currently worth about $1.3 million. Another example is the artificial heart developed at Hershey

Medical Center. William Pierce, Emeritus Evan Pugh Professor of Surgery,

Gerson Rosenberg, Professor of Surgery and Chief of the Division of

Artificial Organs, and their team developed a total artificial heart that

can be implanted in the space created by removal of the patient’s heart.

The system also uses an implanted controller and energy transmission

system. This invention stems from a 25-year-old research activity at Penn

State funded for many years by NIH. Because this technology is now so

advanced, NIH will no longer continue to support development of this

device. Fortunately, an industrial partner and recognized leader in the

field, ABIOMED, was identified to help Penn State researchers continue

their work as they move toward clinical trials of the device. ABIOMED will

have exclusive rights to the Penn State Heart and will have access to

future advances in related implantable replacement heart technology. The

terms of the transaction consisted of payment to PSRF by ABIOMED of 60,000

shares of common stock currently worth about $1.3 million.

As we construct for you our long-term vision for Tech Transfer at Penn

State, we should say a word about Innovation Park. As you know, the Park

was established 13 years ago to serve a variety of functions. As we now

enter the 21st Century in earnest, we are planning for the full

development of the Park. We see Innovation Park as the location for

incubators that will house our start up technologies. We see these

fledgling companies graduating from our incubator to fully contained

companies in more mature space with some of these companies eventually

emerging in freestanding buildings at the Park. In keeping with our

developing concept of the Park, we are in the process of engaging a new

developer who will assist with the completion of the remaining acreage.

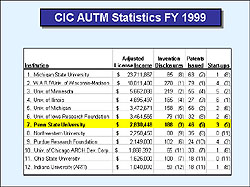

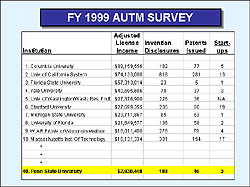

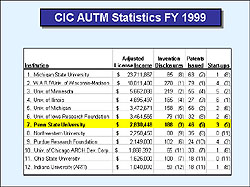

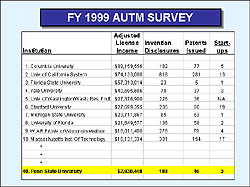

Having provided you with a perspective on

what we have accomplished and where we are going, I would now like to put

our position into a national context. Looking at the 1999 data, within the

CIC we rank 7th in licensing income and 5th in terms of patents issued. At

a national level we rank 40th in licensing income and 16th in terms of

patents issued. It is important to recognize that our position is a

reflection of several points. First, and most importantly, Penn State

became engaged in this game in earnest in the mid-1980s. The University of

Wisconsin began in 1929 with the discovery of Warfarin, a well-known

pesticide, and today a component in a frequently prescribed blood thinner.

Of course, great success can come from hitting the "big one". Florida

State University, which is not amongst the top tier research institutions,

is ranked number 3 in licensing revenue because of one 5-letter word

"TAXOL". A successful technology transfer activity cannot bank on hitting

the big one, but rather must make a concerted effort to disclose, license

and patent a broad range of promising technologies. The differential

between our ranking in licensing income (40th) and patents issued (16th)

in 1999, speaks to the aggressive approach we are taking to this

enterprise, and gives us every reason to predict increased success in the

next several years.

|

|

A final question then, is how will the University benefit from a

successful Tech Transfer enterprise? If we look at The University of

Wisconsin, we can see that their foundation with its $1 billion endowment

got its start over 70 years ago and has been fueled by many successes

starting with the discovery of lWarfarin as I have already said, and

synthetic vitamin D. The royalties from those first discoveries, and

others since that time have generated the endowment, which is now being

used to seed research and fund graduate education. This certainly is our

long-term goal as well.

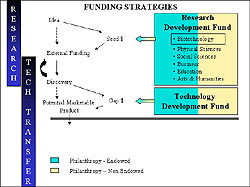

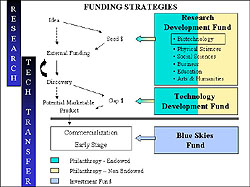

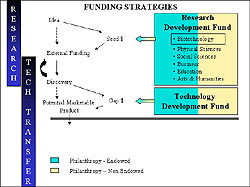

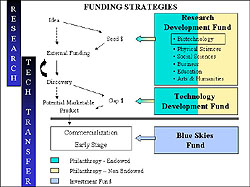

But we find ourselves in a "catch 22".

Before faculty can even secure the grants to conduct the research that

will lead to the discoveries we have talked about this morning, they often

need some seed money to obtain preliminary data necessary in this

competitive environment. And once the key discoveries have been made,

federal funding agencies often are no longer willing to support the

research; however, the technology is not fully developed and so a gap is

created because companies are not yet willing to invest. In a mature

Technology Transfer program, such as we can see in the example at the

University of Wisconsin, the funds provided by the royalties, licensing

fees and sale of equity provide this seed and gap funding. Given our late

arrival in this arena, we are not yet at that point. To help jump start

the system, we have initiated a development project to raise funds for

Research and Technology Development. Time does not permit me to go into

detail describing how we plan to utilize these funds once the money is

raised; but this summary slide helps me show you the three steps, (1)

research, (2) technology development, and (3) commercialization, that

comprise the complete activity, and to suggest to you that we look to a

melding of endowed and nonendowed funds, met later in the evolution of the

intellectual property by investment funds to lead to the economic success

of our technology. Over time, the commercial success will lead to

increased resources for reinvestment in these funds.

|

|

I will end, where I began by suggesting to you that the fruits of our

labors will lead to support for research and education, economic

development in the Commonwealth, and intrinsic value achieved by the

realization of the types of technology we discussed with you today.

Thank you

|

Last year we began the research presentation

with our equilateral triangle. You may recall that we spoke of the three

missions of the University - Outreach, Education, and Research as the arms

of this triangle, with the connections reflecting the integral

relationship amongst these activities. Today, as we make Technology

Transfer the focus of our discussion, we will again begin with the

triangle this time having rotated it to place outreach at the top of the

screen.

Last year we began the research presentation

with our equilateral triangle. You may recall that we spoke of the three

missions of the University - Outreach, Education, and Research as the arms

of this triangle, with the connections reflecting the integral

relationship amongst these activities. Today, as we make Technology

Transfer the focus of our discussion, we will again begin with the

triangle this time having rotated it to place outreach at the top of the

screen.

One of the former interns, Livinia Jones, is now a registered

patent attorney; she was hired by McQuaide Blasko and works closely with

Mark Righter, our attorney of many years. This spring we are embarking on

an interesting experiment. Four undergraduate students from the Department

of English will intern in IPO during the spring and summer semesters. Don

Bialostosky, the Head of the English Department, and Gary Weber conceived

of the idea of utilizing English students skilled in parsing, reading and

understanding complex literature to assist IPO staff in tracking key

concepts through multiple drafts of complex and lengthy agreements,

especially licenses. As we all know, there are many outlets for the

talents of students in English and we hope to open the eyes of some of

these students to a very interesting set of possibilities.

One of the former interns, Livinia Jones, is now a registered

patent attorney; she was hired by McQuaide Blasko and works closely with

Mark Righter, our attorney of many years. This spring we are embarking on

an interesting experiment. Four undergraduate students from the Department

of English will intern in IPO during the spring and summer semesters. Don

Bialostosky, the Head of the English Department, and Gary Weber conceived

of the idea of utilizing English students skilled in parsing, reading and

understanding complex literature to assist IPO staff in tracking key

concepts through multiple drafts of complex and lengthy agreements,

especially licenses. As we all know, there are many outlets for the

talents of students in English and we hope to open the eyes of some of

these students to a very interesting set of possibilities.

Another example is the artificial heart developed at Hershey

Medical Center. William Pierce, Emeritus Evan Pugh Professor of Surgery,

Gerson Rosenberg, Professor of Surgery and Chief of the Division of

Artificial Organs, and their team developed a total artificial heart that

can be implanted in the space created by removal of the patient’s heart.

The system also uses an implanted controller and energy transmission

system. This invention stems from a 25-year-old research activity at Penn

State funded for many years by NIH. Because this technology is now so

advanced, NIH will no longer continue to support development of this

device. Fortunately, an industrial partner and recognized leader in the

field, ABIOMED, was identified to help Penn State researchers continue

their work as they move toward clinical trials of the device. ABIOMED will

have exclusive rights to the Penn State Heart and will have access to

future advances in related implantable replacement heart technology. The

terms of the transaction consisted of payment to PSRF by ABIOMED of 60,000

shares of common stock currently worth about $1.3 million.

Another example is the artificial heart developed at Hershey

Medical Center. William Pierce, Emeritus Evan Pugh Professor of Surgery,

Gerson Rosenberg, Professor of Surgery and Chief of the Division of

Artificial Organs, and their team developed a total artificial heart that

can be implanted in the space created by removal of the patient’s heart.

The system also uses an implanted controller and energy transmission

system. This invention stems from a 25-year-old research activity at Penn

State funded for many years by NIH. Because this technology is now so

advanced, NIH will no longer continue to support development of this

device. Fortunately, an industrial partner and recognized leader in the

field, ABIOMED, was identified to help Penn State researchers continue

their work as they move toward clinical trials of the device. ABIOMED will

have exclusive rights to the Penn State Heart and will have access to

future advances in related implantable replacement heart technology. The

terms of the transaction consisted of payment to PSRF by ABIOMED of 60,000

shares of common stock currently worth about $1.3 million.